The third stage of the Ramat Rachel archaeological project in Jerusalem was completed in November 2002. The site was officially opened to the public with a ceremony at a conference attended by the president of Israel. The site has evidence of several periods of occupation, these include: an Iron Age palace and citadel built, most probably, by the kings of Judea; finds from the Persian and Herodian periods; a villa and baths built by the Roman Tenth Legion; a Byzantine church and monastery; and early Moslem remains [1]. Excavations at Ramat Rachel were conducted primarily in the 1950s by Professor Aharoni and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, in collaboration with the University of Rome.

After 1967 the site was neglected and it gradually disappeared from public consciousness. In 1996, the planning process to re-introduce the site to the public was begun as a joint venture between the Israel Antiquities Authority, the Israel Ministry of Tourism, Keren Kayemet LeIsrael and the neighbouring Kibbutz Ramat Rachel. The cost of the works to date has reached 1.8million shekel (US$400,000), funded mainly by the Ministry of Tourism but also by the other members of the project committee. The realization stages of the project were carried out under the extremely problematic political situation that has existed in Jerusalem since September 2000.

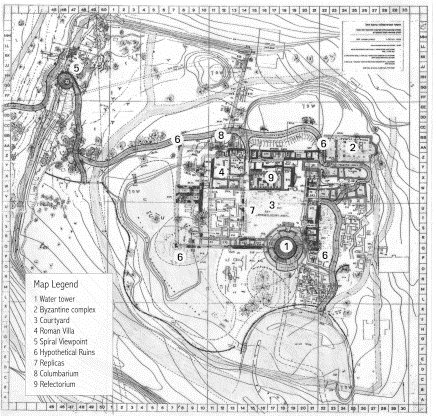

The project for the preservation and presentation of the site at Ramat Rachel (see map in Figure 2) combines archaeological excavations, conservation and development works with the installation of sculptural elements that relate to theories about the site in antiquity. ‘Creative preservation’ [2] attempts to establish a contemporary dialogue with the site and the public, while dealing critically with cultural and ethical issues relating to the preservation of historical memory.

BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE PROJECT’S HISTORY

1996–98

Stage I: preliminary research and planning, retrieving the extremely fragmentary information concerning the excavations and the history of the site in the 20th century, formulation of ideas regarding ‘creative preservation’.

1998–99

Construction of the ‘Spiral Viewpoint’ (in memory of Y. Engel): a sculptural observation point that relates to Aharoni’s theory about the location of the outer citadel wall.

2000

Approval of the five-stage project for the site by a public committee of experts.

2000–01

Stage II: archaeological excavations, site cleaning, conservation work, construction of paths, safety installations.

2001–02

Stage III: construction of the ‘Hypothetical Ruins’, restoration of the Israelite palace courtyard, installation of explanatory signs, development of the site’s surroundings: the western slope walkway, the parking area, etc., opening ceremony.

Planned future stages

Stage IV: Construction of the Museum-Archive in the old water tower at the site.

Stage V: Completion of the walkway on the mountain of Ramat Rachel: a 1.5km path that connects the Archaeological Garden in the west with the Park of Olives in the east.

‘HYPOTHETICAL RUINS’

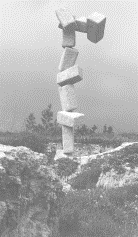

The ‘Hypothetical Ruins’ are sculptural elements that relate to archaeologist Yohanan Aharoni’s theory regarding the Iron Age Israelite citadel. Placed at what are believed to be the corners of the casemate wall (Figure 3) surrounding the late Iron Age palace (7th– 6th centuries BCE), the artificial stones rise – seemingly against the laws of gravity – to the supposed height of the ancient wall. They invoke the memory of the wall’s construction but, at the same time, relate to its

destruction and to the hypothetical nature of the archaeological theories concerning its existence (Figure 4). The suspended hollow ‘stones’ communicate a two-fold approach to Aharoni’s assumptions: making them materially visible while stressing their hypothetical nature; marking the supposed borders of the Iron Age inner citadel yet taking the image of this citadel into the realm of the ‘poetry of ruins’. In contrast to the fabricated stones, every effort has been made to preserve the authentic ones at the site and to leave their ancient existence undisturbed. The passage of time has left its mark on these stones, bearing witness to the irretrievable passing of civilizations.

In her article on the role and methodology of biblical archaeology in the first years of the State of Israel (1950s–1960s), Shulamit Geva [3] points out the compliance of this ‘state archaeology’ with the need to establish ‘ancient roots’ for the new state. Much has been said lately about the hasty manner in which biblical texts have been used for the direct interpretation of archaeological finds [4]. The role of the ‘Hypothetical Ruins’ is not to enter into the archaeological– ideological (Zionist–post-Zionist–post-modern) debate, but rather to suggest the existence of these discussions (and others) within the context of the actual site.

THE COURTYARD OF THE IRON AGE ISRAELITE CITADEL

The conservation approach used at the site does not favour restoration. It is maintained that the charm, strength and moral validity of archaeological finds depend primarily on their authenticity; reconstruction, it is argued, creates an illusion of certainty that is incompatible with the hypothetical nature of archaeological theories. However, floor levels at archaeological sites depend largely on the excavators’ decisions, which are based on their specific agendas. The modification of floor levels to allow for their presentation may be considered a more valid intervention – one that does not alter the ‘original’ any more than does the process of excavation itself.

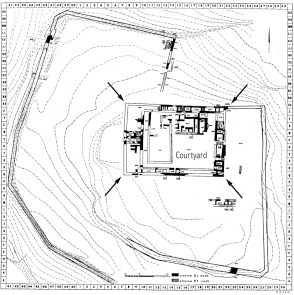

The centrepiece of the site’s conservation project is the ‘restoration’ of the courtyard space of the Iron Age Israelite citadel – a rectangular surface paved with

crushed limestone, measuring 23 ´ 29.7m2 (Figure 5). The two main buildings of the palace stood at the northern and western ends of the ancient courtyard. The ‘restoration’ is based on Aharoni’s excavations, which cleared the courtyard of all remains from the later periods. At the courtyard’s western end, some of the original pavement was left exposed and in other parts the earth was levelled and compressed with a soil stabilizer (RBI81) [5]. At the supposed location of the western building, three replicas of a Proto-aeolic capital found in situ (now on exhibition at the Israel Museum) were placed on steel rods among piles of original ashlar stones (Figure 6). This installation, based on the studies of Y. Shiloh [6], is meant to give the visitor a general sense of the findings on location.

SPIRAL VIEWPOINT

The ‘Spiral Viewpoint’ (Figure 7), in memory of Y. Engel (1999[AUQUERY4]) is a sculptural observation point overlooking the cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem [7]. The structure’s general plan is reminiscent of the Proto- aeolic motif and relates to Aharoni’s theory concerning the outer Israelite citadel wall. The Spiral Viewpoint was built at what is thought to have been the top of the ancient wall, four metres above its excavated foundations (part of which was exposed in the course of the project), thus commanding a panoramic view of the surroundings.

EXPLANATORY SIGNS

Approximately thirty signs with explanations in Hebrew, English and some in Arabic, were installed at the site. Five include detailed information about the history of the site (with plans and photographs) divided into the main periods of occupation (Israelite, Roman and Byzantine); other, smaller, signs were placed near the various structures, offering a brief note about their chronology, use and proposed dating. It was decided that in order to raise visitors’ awareness of the complexity and diversity of the finds, as well as their multicultural aspect, it was more important to present accurate details and information than to simplify and generalize for touristic purposes.

PRELIMINARY EVALUATION OF THE WORK: CREATIVE PRESERVATION AND PUBLIC IMAGE, ZIONIST ARCHAEOLOGY AND THE POETRY OF RUINS

The Ramat Rachel archaeological site was reopened to the public in November 2002 after many years of neglect. One of the major goals of the conservation project was to re-introduce the site into public awareness. This may have been achieved by the mere fact that the opening ceremony was attended by the president of Israel; by the publication of an informative catalogue [8]; and by the media exposure that ensued. Preservation, especially today, seems to be closely related

to a public image that can give value to historical memory. Judging from the damage done to the site in the years of its neglect, it seems that even the very existence of sites is largely dependent on this public image. ‘Creative preservation’, in its capacity to arouse public interest, may be a useful tool of conservation in this sense.

I perceive the application of ‘creative preservation’ at the site in very broad terms; the ensemble of interventions (the sculptures and the viewpoint, as well as the ‘replicas’, paths and signs) is aimed at creating an environment. Moreover, I believe that the process of approaching bureaucratic institutions with an idea, and enabling them to collaborate and find support for the realization of such an artistic concept, is also part of ‘creative preservation’. The incorporation of contemporary sculpture into an archaeological site was not done to apply artistic possibilities to a new venue, but rather as an innovative means of interpretation to promote the site’s presentation and conservation. The ‘environmental interventions’ do not use archaeological remains as a background, but rather attempt to convey the complexity of the archaeological activity and penetrate, perhaps, some of the mysteries of the place. The sculptural elements that make use of the frequently repeated image of the suspended artificial ‘stones’ focus on the theories about the Iron Age citadel. This sole remnant of a complete public building complex from this period in the Jerusalem area [9] is largely responsible for the significance that Ramat Rachel has in archaeological circles. The sculptures attempt to convey to the visitor the location and scale of the ancient palace, according to Aharoni’s theories, which otherwise would not be clearly visible at the site without guidance. At the same time, these ‘sculptured stones’ present a critical view of the excavation process and of archaeological theory itself. The decision to conserve the water tower from the 1950s (as a representation of the Zionist layer in the site’s history), and the critical notion implied by ‘Hypothetical Ruins’, may bring to the fore discussion of Aharoni’s alleged ‘Zionistic inclinations’ and the role of archaeology in the formation of Israeli identity in the last century. This dimension adds a contemporary cultural value to the experience at the site. The ‘Hypothetical Ruins’ attempt to offer another perspective to the story of Ramat Rachel and, as N. Silberman points out [10], may therefore be connected, above all, with the previous teller of the story – Yohanan Aharoni. The focus on the Iron Age citadel (and on its connection to 20th-century interpretation) was consciously balanced by the planning of the paths and signs at the site. Visitors are guided through the main features of the other periods of occupation (such as the Roman villa, the refectorium of the Byzantine monastery and the columbarium), which were conserved and presented clearly with detailed signs.

Ideally, ‘creative preservation’ could provide a

perfect marriage between artistic significance and the conservation of archaeological values. In practice, however, a certain physical and symbolic balance has to be maintained. I believe that the artistic elements introduced (or any other creative intervention, for that matter) should not overpower the impact of the finds, but should enhance the experience created by the archaeological surroundings. Bearing in mind Diderot’s ‘Poétique des Ruins’[11], my ultimate goal at the site was to create (or retrieve) a total feeling of the place, an ambience, a delicate sensation triggered by diverse factors, not all of which are clear and tangible.

The nature of realizations is, perhaps, that they can take an independent course, transforming preliminary intentions and goals. Various practical, bureaucratic and local considerations at Ramat Rachel restricted our initial conception. One major regret in the project is that, because of last-minute financial limitations, the plans for the Byzantine complex at the eastern end of the site were not carried out (hopefully this will be done in the future).

The Archaeological Garden has been open to visitors for a few months now. Respect for nature and for the past, and an awareness of the multicultural history of the place (as seen in a specific location), might afford another perspective on the current national and religious conflict in this region. Although foreign tourism in Jerusalem is presently almost nonexistent, the site is nevertheless visited by local inhabitants. Perhaps there will be a more substantial evaluation of the work at the site by the public in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank some of the many people who made the Ramat Rachel project possible: J. Seligman,

R. Alberger, G. Solimany and G. Avni from the Israel Antiquities Authority; N. Peretz, L. Yadin and D. Mingelgreen from the Israel Government Tourist Corporation; J. Rotlein and G. Avni from Keren Kayemet LeIsrael; A. Dahan, D. Ben Shushan and J. Engel from Kibbutz Ramat Rachel; R. Garboa, A. Abayat, S. Abu Tir, A. Hason, [AUQUERY6]Zagai, O. Reizman and H. Davis for their assistance in the project’s execution; and G. Scichilone, G. Garbini and many others for their ongoing encouragement from Rome.

Ran Morin [AUQUERY7]

Contact details: 38/7 Street of the Prophets, Jerusalem 95103 Israel. Tel/fax: + 972-2-6250938; email: ranmorin@netvision.net.il

REFERENCES

- Aharoni, Y. Excavations at Ramat Rachel – Seasons 1959–1960. Rome (1962); Seasons 1961–1962.

Rome (1964).[AUQUERY1] - Morin, R. Creative preservation. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 3(4)

(1999).[AUQUERY2] - Geva, S. Biblical archaeology in its first steps. Zmanim 42 (1992) 93–102. Geva suggests that Aharoni’s famous personal rivalry with Yadin (uncontested leader of this trend of ‘state biblical archaeology’) had a deeper methodological basis. At Ramat Rachel, Aharoni put aside his earlier broad survey approach and, backed up by direct correspondence (unpublished) with Prime Minister Ben-Gurion, instead focused on a large-scale test excavation of an Israelite palace, similar to what Yadin had done in his archaeological activity. Thus, theoretically, Ramat Rachel could be seen as a typical case of Geva’s ‘root supplying’ archaeology, although in practice things are not so evident. Aharoni’s German–Jewish punctiliousness and professionalism (often confirmed by his Italian collaborators) and the high-level international crew at the site mean that his excavations and assumptions were scientifically well founded.

- Finkelstein, I. and Silberman, N.A. The Bible Unearthed. New York (2001).[AUQUERY3] In this light, one may compare Aharoni’s much contested identification of the Iron Age citadel at Ramat Rachel with the palace of Jehoiakim, based on a passage in Jeremiah 22: 13–19.

- The soil stabilizer was mixed in a 15cm-thick layer of loose local earth (some added from the nearby excavations) and compressed to form a solid uniform water resistant/weed resistant surface, resembling in colour the local chalky earth (and not a type of pavement).

- Shiloh, Y. The Proto-aeolic Capital and Israelite Ashlar Masonry. Jerusalem (1979).[AUQUERY3] The installation is much less a ‘sculpture’ than the ‘Hypothetical Ruins’ and much closer in nature to the explanatory signs.

- See note [2].

- Morin, R. The Archaeological Garden at Ramat Rachel, Jerusalem. Jerusalem (2002).[AUQUERY3]

- According to Dr G. Avni of the Israel Antiquities Authority (personal communication, October 1997).

- Silberman, N. ‘From Masada to the Little Bighorn’, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 3(1) (1999).[AUQUERY2] ‘The real meaning of our modern archaeological stories and reconstructions, I would argue, is directed less toward our remote ancestors or the general public then towards the previous tellers of the same tale.’ (p. 14)

- Diderot, D. Salon de 1767. In: Seznec, J. and Adhémar, J. (eds) Oxford (1983) III,

227.[AUQUERY5]