ABSTRACT

The article proposes “Creative Preservation” as an artistic approach to contemporary questions concerning the preservation and presentation of archaeological sites. By examining critically the role of cultural heritage today, it attempts to search for alternative perspectives and to retrieve forgotten sensibilities such as Diderot’s “Poetics of Ruins”. It first examines concepts of time and authenticity, especially in archaeological sites, as interpreted by various authors from Poincare, von Schiller, Bergson and Simmel to Choay and Jokilehto. Dedicated to immaterial qualities of places, “Creative Preservation” suggests the refinement of “images of authenticity” in an attempt to penetrate and to communicate with deeper levels in the complex reality of ancient places – actual and specific locations which anchor and root memory in material.

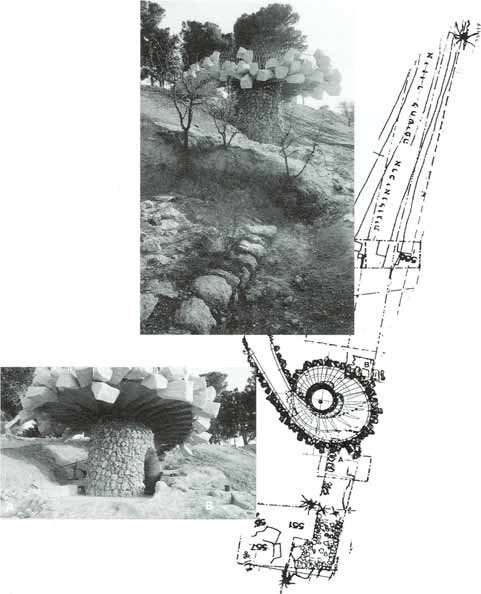

A first realization of this approach is presented in the form of the spiral viewpoint recently constructed at the northwest part of the archaeological site of Ramat Rachel near Jerusalem.

Cultural circles at the end of the twentieth century, especially in Europe, are obsessed with preservation. Indeed, one feels a general assault on humanistic values, the natural environment and on our cultural heritage, an attack led by savage economic forces armed with global communication networks and an unrestricted technology. The dangers are so great, and the siege so severe, that many conscientious people have developed a ‘preservation instinct’, much in the way our body produces antibodies to infection. But the question of preservation is a very complex one. Can authenticity really be preserved? Doesn’t the mere intention of doing so spoil its ‘naivete’ (in Schiller’s terms [1]) and thus make it impossible? In her penetrating analysis of the contemporary role of

cultural heritage, Francoise Choay presents the main

themes of the ‘false discourse’ concerning its preservation. ‘Culture has become an industry, which transforms, packages and diffuses heritage for consumption’, while ceaselessly engaging in ‘the planetary process of banalization and normalization of societies and their environment’. Paradoxically enough, this process is self destructive since the more these ‘patrimonial practices’ are successful, the less ‘authentic’ this same heritage, its raw material, becomes. Also self-destructive, from a broader point of view, seems to be the western impetus in establishing a universal historical timeline, ‘ceaselessly refined by archaeology and the human sciences’, in the sense that the qualities of its basic unit, time, have been put in serious doubt by concepts of modern physics and by relativist philosophy. Henri Poincare, treating the question of time in his original and lucid way, concluded that for us there can be no ‘true’ definition of time and of its qualities. Furthermore, it cannot be measured objectively, as a result of which we are forced to adopt the following definition:

The simultaneity of two events, or the order of their succession, the equality of two durations, are to be

so defined that the enunciation of the natural laws may be as simple as possible. In other words, all these rules, all these definitions are only the fruit of an unconscious opportunism. [3]

Scientists of our century tell us that time cannot be defined, but in order to make some sense of our physical world we can adopt convenient definitions at will, definitions that can preserve our simple laws of physics and allow us to measure facts that ‘transpire in different worlds’ (and which cannot be truly compared). This definition is far from the image of a Greek Chronos, a mighty Titan regulating the universe with majestic certainty.

Taking Poincare’s ideas away from the direct physical world, are we, under these conditions, to measure the time of civilizations, landscapes, works of art and human beings on the same scale? And if we did (as we certainly do all the time), what would we gain by it?

The great advances of physicists in the beginning of this century are beginning to take root in our most basic cultural conceptions and phenomena. If we define time and space according to convenience, regardless of an external truth and harmony, can we not construct virtual realities, independent of nature and her inconvenient contradictions, realities in which we feel perfectly confident and safe in our

knowledge? We tend though to suspect this virtual knowledge profoundly and there are strong indications (such as a global wave of religious revival) that we are losing even the certainty of uncertainty.

All this can be elaborated much further, but coming back to our ‘preservation instinct’, we can at least admit that its particular force and necessity in our time is linked to the destruction of absolute time. A rapidly changing and ‘relative’ world thus turns our heads and we try to stop and hold on to anything we can at its known state. Is this frantic action any help? Are we to regain a harmony with nature and within our souls (in Platonic terms) or, aiming much lower, can we at least establish some significant concepts that might serve as a basis for a contemporary appreciation of our existence?

Where are we to look for counsel if not in our past and in nature? But in order to get anything from these eternally fleeting entities, we have to re-learn how to listen carefully and try to find a language to speak with them, because our language has become too arbitrary and vulgar (i.e. virtual). This is difficult, if not impossible.

What is needed, if we are to re-establish a meaningful contact with our past and with nature, is a creative process which will draw its inspiration directly from authentic and specific phenomena, a particular case, not an image or a generalization. If from this specificity we can draw some syllables for our language, we will be on the right track, and even our inferences and generalizations will regain some rigour.

What is synthetic understanding in a world divided into endless bytes? In order to recreate this link, we need to be able to put things together again, different and unexpected things, and not divide them up endlessly.

THE POETICS OF RUINS

Nous restons seuls de toute une génération qui n’est plus; et voilà la première ligne de la poétique des ruines. [4]

Diderot’s inspiration in his treatment of ruins is a remarkable example of an approach to the past and to what we call archaeological sites of another

time. Most of his texts on the subject are related to his impressions from the paintings of Hubert Robert (creator of romantic landscapes with ruins). The ruin is the embarkation point for a creative, philosophical and artistic voyage in the passage of time; not lighthearted travels but rather melancholic expeditions of contemplation of lost civilizations, crumbled grandeur and the futility of man’s works. So possessed is the traveller that he projects his mood onto a similarly lit future.

Nous anticipons sur les ravages du temps, et notre imagination disperse sur la terre les édifices mêmes que nous habitons. A l’instant, la solitude et le silence régnent autour de nous. Nous restons seuls de toute une génération qui n’est plus; et voilà la première ligne de la poétique des ruines. [4].

This frame of mind prefers ruins to the original structures, a notion in opposition to the role of ‘historical testaments’ which they represent for archaeologists and their science, and which they held for humanists in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries [5]. The ‘poetics of ruins’ gained importance at the end of the eighteenth century, especially in France (but also elsewhere), in the works of several poets and painters and were carried into practice in Romantic gardens where artificial ruins were constructed to enhance the landscape.

Diderot’s poetics of ruins teaches us about the appreciation of ruins for their own sake. A striking fact about this notion is that Diderot’s ruins are not actual ruins (although he mostly refers to the ruins of Rome), but rather artistically transformed ruins, in the world of painting and especially in the realm of ideas.

AUTHENTICITY: RUINS AND NATURE

… authenticity is ascribed to a heritage resource that is materially original or genuine (as it was constructed) and as it has aged and changed in time… four aspects of authenticity should be considered:

Authenticity in design Authenticity in materials Authenticity in workmanship Authenticity in setting. [6]

…le charme de la ruine consiste dans le fait qu’elle présente une oeuvre humaine tout en produisant l’impression d’être une force de la nature… La nature fait de l’oeuvre d’art la matière de sa création à elle, de même qu’auparavant l’art s’était servi de la nature comme de sa matière à lui… [7]

A ruin’s authenticity, it seems, is closely associated with the process of its assimilation into nature. From this transformation over the centuries, its ‘authenticity’ gains its validity and its charm, thus acquiring nature’s ‘naivete’ (in Schiller’s terms), ‘of nothing but the voluntary presence, the subsistence of things on their own, their existence in accordance with their own immutable laws’. [8]

This happens quite independently of the ruin’s original purpose and the will that created it. And indeed, one can feel intuitively [9] that this ‘true spirit of authenticity’ is a fleeting spiritual existence, an invisible entity residing with scattered rocks, overgrown weeds, solitude, neglect and abandon. The moment man steps back into the scene, as restorer, preserver and even as a visitor, the charm is gone, and we are left with better or worse imitations or images of the authentic spirit.

Re-examining ICCROM’s definition of authen- ticity in this light, I am tempted to add a fifth aspect to authenticity: authenticity in spirit. This aspect contains, to a degree, all the other aspects but seems also to be independent of them. In fact, one may suspect that this true spirit of authenticity is not closely dependent on the ‘materially original or genuine’ but rather on a feeling that springs from a present state, not from a past reality.

AUTHENTICITY IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES

… N’oubliez pas que c’est une hypothèse, et qu’elle traduite simplement certaines propriétés de faits tout particuliers, découpés dans l’immensité du réel … [10]

The archaeological site is a special case with regard to its preservation and presentation. Instead of being presented as an original, more or less deformed by the passage of time (as an historical building or a

work of art), an archaeological site is a secondary image. The first to approach it are the archaeologists (often different individuals and during different periods) who claim the site for their science and make use of it for their interests. Their activity produces extensive changes. The shovelling of quantities of earth, often dumped near the excavations, causes major topographical transformations. Archaeological digging is stratigraphical, usually resulting in the elimination of the ‘higher’, more recent strata, and always in the disappearance of the ‘patina of time’ formed on weathered surfaces over the centuries. Archaeologists are usually limited by the lack of money and time, keeping their projects eternally incomplete and subject to priorities and, like most professionals, they tend to quarrel with each other, resulting in the fact that much of the documentation concerning their aims and achievements is unavailable or misleading.

All this archaeological activity, done more or less in good faith (as are all human works), is ideally aimed at establishing the ‘scientific image’ of the site, that is the reduction of its reality to tangible facts based on material proof. No doubt it is a very important image, since it is abstracted enough to be compared and accumulated and is subject to falsification. But it is only a partial and incomplete image of the site’s ‘immense’ reality, and not the only one of which humans are capable.

The archaeological site seems to be a hybrid of actual material testimonies (revealed or buried), a natural environment and immaterial elements such as its history, its significance and its ambiance. This hybrid is created, above all, by violent human intervention, the archaeological excavations.

A faithful representation of a site, dedicated to its ‘authentic’ qualities, meaning its total reality, has to keep in mind not only the archaeological image (while taking care to understand its bias) but also to consider its other aspects, including the intangible and irreducible nature of the place, which the ancients often worshipped as a divinity.

CREATIVE PRESERVATION

The aim of modern restoration is to reveal the original state within the limits of still existing material. [11]

Indeed, creative preservation is a contradiction in terms, are we to create something new in order to preserve the existing? First it should be stated that one can fully understand, justify and support ICCROM’s strategies and regulations for the pres- ervation of world heritage sites. The immediate physical dangers which these sites face daily, from immensely powerful forces, justify any precautions. But the question may be raised, is it enough to save the sites? Now that the patient’s life is assured and he can even walk and eat, wouldn’t we also want him to speak and smile?

In restoration and in the preservation of ar- chaeological sites, there can be no question of ‘true authenticity’ (which might be achieved by nature if a site is abandoned completely). Our scope in this activity is rather limited to creating images of authenticity which depend, like all images, on the degree and refinement of the art applied. Nevertheless, if we are to accept Schiller’s word, this image-creating activity is not without possibilities.

Since nature can be aesthetic only as an object of free contemplation, her imitator, creative art, is completely free, because it can separate from its subject matter all contingent limitations, and also leave the mind of the observer free because it imitates only the semblance, and not the actuality. Because the whole magic of the sublime and the beautiful subsists only in semblance, art thus possesses all the advantages of nature. [12]

On archaeological sites, what can be seen and what is interpreted conveys, in the main, the state of the excavations dependent on the archaeologists’ aims and limitations. Are we to preserve this aspect (undoubtedly an interesting one) rather than aspects of the passage of time and of the existence of living men over the centuries? Furthermore, the ‘existing material’ in a site is far from an innocent and natural representative collection, and is also hopelessly mixed with non-original or irrelevant material and with a changing contemporary setting. Wouldn’t this state require an active intervention in order to balance the ‘inauthentic’ dynamic forces? Or, to put it in Lampedusa’s terms, if we want everything to remain, maybe first everything has to change?

The challenges and the risks in creative preser- vation are great. Its success depends on our ability to communicate with the past and with nature which has taken over the works of man. We are to create an image of a site’s ‘true spirit of authenticity’ to translate immaterial qualities into a form that human beings can feel and perceive.

CONCLUSION

“…car le souvenir, représente précisement le point d’intersection entre l’esprit et la matière.” [13]

Ruins seem to be losing much of their age-old appeal to a contemporary public which no longer has the patience and the cultural background required in order to appreciate them. In a time when the Italian Minister of Culture commissions Disneyworld experts to advise on the interpretation of Pompeii and when the Louvre may be visited through the Internet and CD-ROMs, it seems legitimate to explore seriously a creative, artistic approach to the preservation and presentation of archaeological sites.

Creative preservation aims at communicating with the past and with the public in a direct way while taking care to respect and understand scientific archaeological knowledge, avoiding banal packaging in the form of easily digestible cultural products. It pursues the site’s ‘authentic’ qualities while keeping in mind the philosophical implications of this activity in a contemporary context.

There exists today a practical need to make many archaeological sites more lively and a willingness of the authorities to do almost anything that can make them economically independent. Creative preservation should not be regarded as a form of animation for tourists aimed at marketing a site in a more attractive way. It may, though, make a site more lively and attractive to visitors by awakening a longing for lost truths and past times, by engaging in a creative process, a living memory.

One may still believe archaeological sites to be mines for excavating lost authentic realities and genuine collective memory. In fact, seen in this light, they provide a possibility of escape from a labyrinth of virtual knowledge and experience which plagues our contemporary existence. Far from being, dreary

locations containing piles of stones in which we are instructed about an official (western) ‘universal version of objective memory’, they can instead become starting points for voyages into the mysteries of the passage of time and into vast and unexplored regions of reality. In a sense, these places are treasures of the rigorously authentic, actual and specific locations which anchor and root memory in material.

The conceptual range in which the word and concept practice have their proper place is not primarily defined by its opposition to theory as an application of theory … Practice as the character of being alive, stands between activity and situatedness. [14]

What does it mean to say we suppose that a wall existed in this location two thousand and six hundred years ago? In what way does this proposed archaeological information relate to our present experience of the place? Where do the borders lie between what is natural and what is ‘artificial’ or ‘man-made’? In what way can a hypothesis acquire a material reality (without it being affirmed as a positive truth)? Can we still recognize in places qualities which defy material and maybe even the ‘abstractions of time and space’ [15]? These may be among the questions which this artistic- archaeological ‘creative intervention’ attempts to suggest.

SPIRAL VIEWPOINT, AT THE SUPPOSED LOCATION OF THE IRON AGE CITADEL WALL

At tbe archaeological site at Ramat Rachel Jerusalem, (in memory of Y. Engel) 1998-9

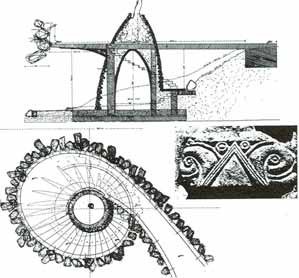

Steel, concrete, artificial stone, flint stone, oak tree, hyssop. Spiral diameter – approximately 7m.

BACKGROUND

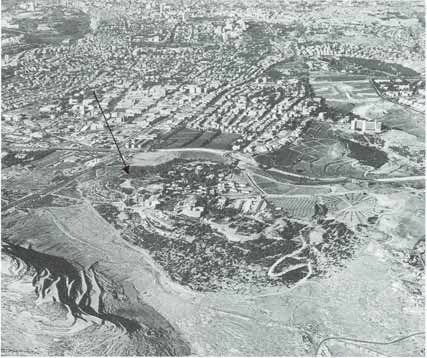

The archaeological site of Ramat Rachel, Jerusalem, is one of the more significant historical locations in the Jerusalem area. It includes an Iron Age palace and citadel built by the Kings of Judea, Persian period and Herodian period finds, a camp and baths of the Tenth Roman legion, a Byzantine complex including a church, a monastery and agricultural

structures and some early Arab remains. Since the ninth century BC, various military and agricultural settlements have been established at this vantage point (820m above sea level) situated midway between Jerusalem and Bethlehem, overlooking these cities and an ancient road junction where the Royal Road leading to Jerusalem from the south was crossed by the road leading west to the coastal plain and by the route running eastwards to the Judean desert and the Dead Sea.

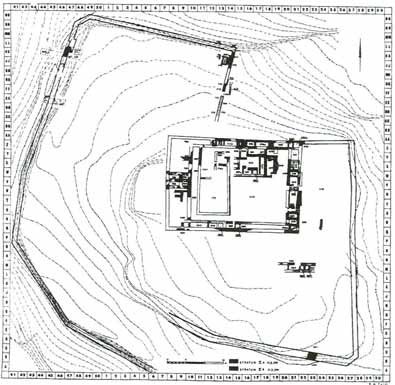

The major excavation work done at the site was conducted by Professor Y. Aharoni in the years 1954 and 1959-62. In the last three seasons the Hebrew University was joined by an expedition from the University of Rome which published three extensive books on the site [16]. Finds from Ramat Rachel are exhibited in the Israel Museum, the Rockefeller Museum and the Museum of the University of Rome. Professor Aharoni identified Ramat Rachel as the biblical Bet Hakerem and the construction of the palace was attributed to King Jehoiakim (608-597 BC). Other researchers disagree with these arguments, and questions concerning the site’s identification and exact dating are still debated.

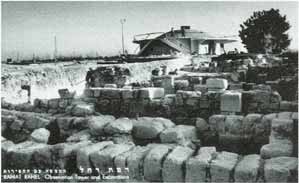

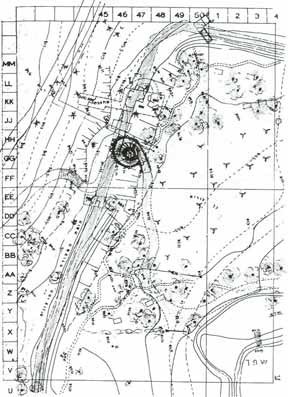

In 1956 an observation point was constructed on the water tower near the excavations, and the site attracted visitors mainly due to the view towards Jordanian territory (Fig. 1). Since 1967 the place has been neglected and gradually disappeared from public consciousness. In 1996, R. Morin was commissioned by the Israeli Antiquities Authority and Kibbutz Ramat Rachel to study the site and to draw initial ideas and plans for its preservation and presentation with a view to its re-opening to the public and in connection with a larger tourist and environmental project for the mountain of Ramat Rachel [17]. The first stage of the work, evaluation for conservation, consisted of the collection and study of the much dispersed (if not intentionally withheld) material concerning the excavations and the findings (in Jerusalem and in Rome), and in the identification of the main values of interest of the site. In parallel, a more theoretical activity was conceived, related to the meaning of the problems presented by the site, and to the significant cultural questions connected with its ‘preservation’ and its re-introduction to the public.

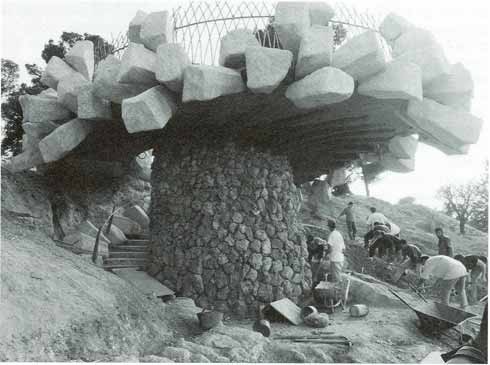

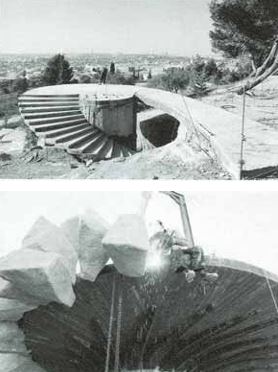

The project is a joint venture of the Israel Antiquities Authority, the Israel Ministry of Tourism, the Engel Foundation (in memory of Yair Engel) and Kibbutz Ramat Rachel. Actual work on the site started in May 1998 (after planning and procedural stages) and involved, apart from the artistic construction, further stages of archaeological excavations (Fig. 2). The viewpoint was opened to the public in June 1999.

SPIRAL VIEWPOINT

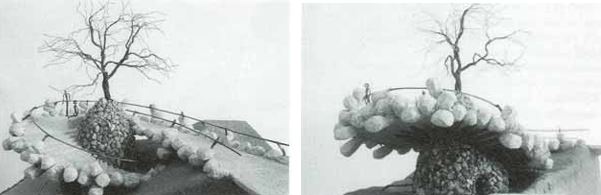

Spiral Viewpoint is located at the northwestern edge of the archaeological site of Ramat Rachel, a point commanding a striking view of the cities of Bethlehem and Jerusalem (Fig. 3). The spiral structure with a transplanted oak tree at its centre connects the upper part of the site, 815m above sea level, on an ancient, artificially-levelled platform thought to have been a military concentration zone, with the foundations of the Iron Age outer citadel wall (811m elevation) which was partially uncovered and reconstructed graphically by Professor Aharoni after his 1962 excavations [18] (Figs 4 and 5). The excavations conducted in connection with the project support Professor Aharoni’s much disputed reconstruction.

The artificial ‘sculpted’ stones are suspended from the spiral structure, reminiscent, in shape, dimensions and material, of the ‘authentic’ building blocks which were carved at the site and used for the ancient fortifications clearly visible nearby (Figs 6, 7 and 8). Artificial in material, speculative and imaginary in their placement, these suspended stones attempt to spin a thread of memory leading to ancient realities of this unmoved (and rigorously authentic) location. By reconstructing the spatial point where the top of the wall is supposed to have existed, and thus giving a sort of reality to the archaeological hypothesis, a visitor will be able to experience directly the strategic qualities of the site. This might clarify on an intuitive level what motivated Judean kings, later Persian officials, the Tenth Roman legion, Byzantine monks and, in the 1920s, a Jewish kibbutz, to establish a hold on this point which has been the site for many battles (the nearby military outposts of the most recent battle in 1948 are clearly evident) over the course of nearly 3000 years.

Spiral Viewpoint may be seen as a first realization in the path suggested in Creative preservation, but perhaps in an ancient sense of the relation between theory and practice described by Gadamer. The theoretical ideas serve only as a guiding sensibility of a vital process of an attempt to establish meaning and to create ‘living memory’, while being subjected to the particular circumstances of a specific location.

The project has already created a renewed interest in the site by the public, the local inhabitants, the media and the government authorities, which have recently funded an extensive cleaning of the excavations and are currently discussing plans for the conservation of the site. But at best the Spiral Viewpoint may communicate an appreciation and a sense of respect for the enigmatic, authentic and infinitely complex qualities of an ancient place, and serve as an invitation to some mysteries of the passage of time.

Ran Morin is an environmental sculptor who has created ‘architectural and organic environments’ which often make unconventional uses of plants and trees. A graduate of the School of Visual Arts in New York City, where he worked and exhibited for a number of years, his realizations are located in Israel, the U.S. and England. He is currently working on projects in Israel and in Europe. At Ramat Rachel Jerusalem he created the “Park of Olives” – a five- hectare artistic environment (1987-1997).

Contact address: Ran Morin, Environmental Sculp- ture and Planning, 38/7 Prophets Street, Jerusalem 95103, Israel. Tel/Fax: +972 2 6250938.

To name only a few: (in Rome) Prof. G. Garbini, Dr. J. Jokilehto, Dr. G. Scichilone, (in Jerusalem) Prof. M. Dubois, Prof. E. Stern, Dr. G. Avni, (in Mount Athos) Father Makarius, and many others. I would also like to thank the America Israel Cultural Foundation for a grant received for this purpose.

REFERENCES

- von Schiller, F. Naive & Sentimental Poetry, F. Ungar, New York (1966).

- Choay, F. L’Allégorie du patrimoine. Paris (1991), pp. 162-64.

- Poincare, H. Tbe Value of Science, New York (1921),234.

- Diderot D. Salon de 1767, ed. Seznec,t III..

- Mortier, R. La poétique des ruines en France. Genève. Lib. Droz Geneve (1974).

- Feilden, B.M &. Jokilehto, J. Management Guidelines for World Cultural Heritage Sites. ICCROM, UNESCO, Rome (1993), 17.

- Simmel, G. Melanges de philosophie relativiste, Lib. Felix Alcan Paris (1912), 120.

- von Schiller, F. Naive & Sentimental Poetry, New York (1966), 84.

- I had an experience of this sort when visiting the scandalously deteriorated, but genuinely enchanting ruins of Ani, a medieval Armenian city now in eastern Turkey, and later on visiting well-tended similarly

- constructed Armenian churches in the republic of Armenia. In the latter, the beauty of form remained impressive but the authentic charm was hopelessly gone.

- Bergson, H. Durée et simultanéité,, P. U. de France, Paris (1922), 160.

- Feilden, B.M &. Jokilehto, J. Management Guidelines for World Cultural Heritage Sites. ICCROM, UNESCO, Rome (1993), 63.

- von Schiller, F. On the Sublime, F. Ungar New York (1966), 212.

- Bergson, H., Matière et mémoire, avant – propos (7 ed.), P.U. de France, Paris (1908). Gadamer, H. -G. Reason in the Age of Science, Cambridge, Mass. (1981), 90.

- Leibniz, G. W. New Essays on the Human, Understanding Philosophical Writings, J.M. Dent & Sons London (1934), 172.

- Aharoni, Y. Excavations at Ramat Rahel – seasons 1959-1960. Rome (1962); Seasons 1961-1962. Rome (1964); 11 Colle di Rachele. Roma (1960).

- The project for the hill of Ramat Rachel is a long-term plan to integrate its various points of interest from its eastern part, Olive Columns and the Park of Olives (a five hectare artistic environment by Ran Morin:1987– 97), through the central tourist complex and onto the archaeological area and the western slope.

- Aharoni, Y. Excavations at Ramat Rahel – seasons 1961-1962. Roma (1964), 51-54.